Fullstory’s Security Engineering team recently conducted a multi-month research project to determine the breadth and cause behind a growing number of domains with names and content impersonating relationships to popular open-source projects and free software applications.

During this blog post we’ll share how we came to learn about this concerning campaign, the analysis involved to determine the purpose of these domains, the scope-and-scale that was discovered, and what actions we took to help the impacted free software community projects.

It started with an email…

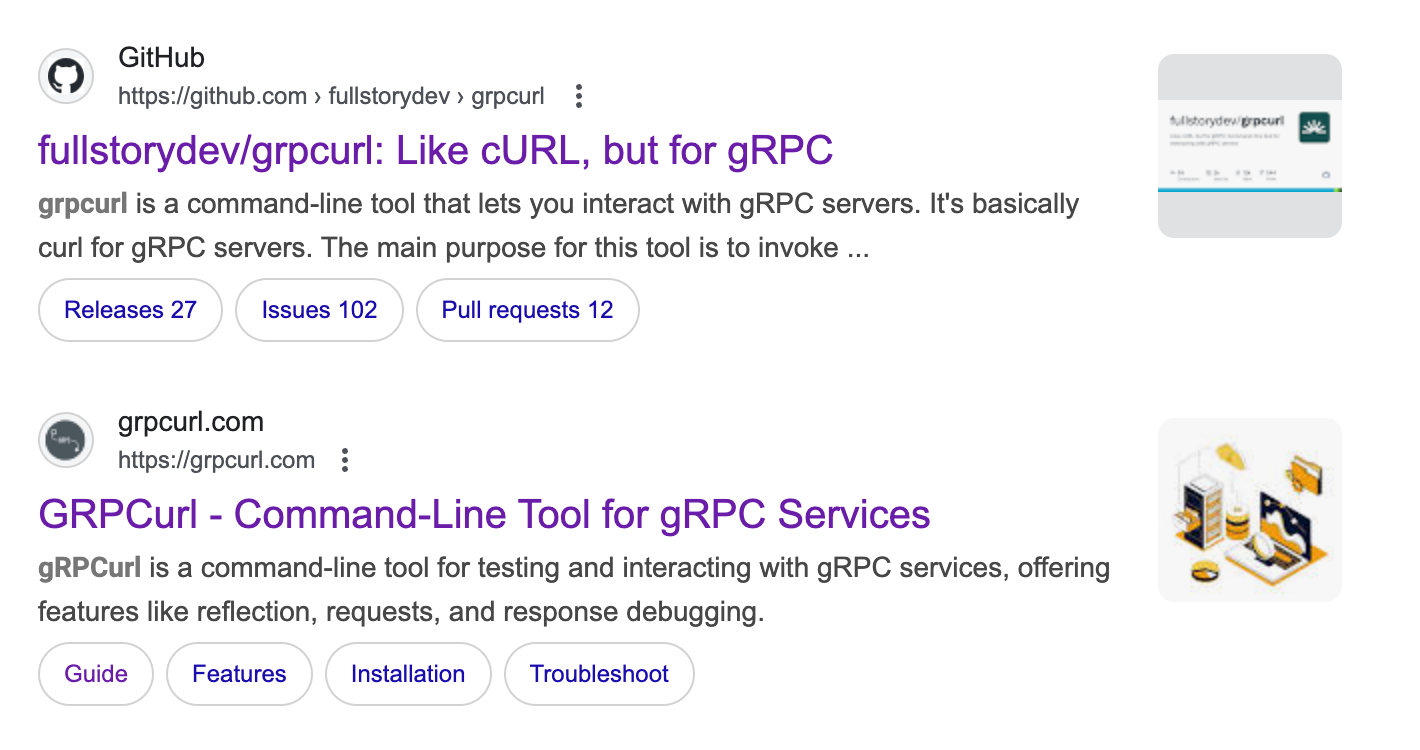

Our analysis began on September 25th, 2025, when an individual alerted us about a domain pretending to be related to our open-source project, gRPCurl. We determined that not only had this web site – grpcurl[.]com ☣️ – created a domain name for our project, but the site was also hosting a copy of our main branch directly on the site and used project content (e.g. Issues) as well to populate it to provide more substance it was official.

More concerningly, however, was that this fraudulent web site ended up being the second search result for our project on Google, looking to be an official site related to our project.

This made it clear that this site was intending to use the name and content from our project to confuse would-be users that may come across this site in their search for our project. At that point we decided to determine if this was a targeted effort towards our company, or a larger pattern. We also wanted to understand the reason behind this as there is clear potential for a bad actor to use this site for phishing campaigns or watering-hole attacks using this domain.

Evaluating impact to our project

Our first analysis of the fraudulent web site was to rapidly understand any obvious abuse. We downloaded the site’s hosted copy of /wp-content/uploads/07/2025/grpcurl-master.zip and extracted the zip, taking a hash of every file within the archive. This hash list was compared to known-good hashes from our project and all matched as expected. Importantly, we also did not find any unexpected files in the archive that would have been added. At this point, we could at least assert that the hosted content was not actively malicious – of course this could change at any time, so we only concluded that at our time of review the archive didn’t contain clear harm.

By reviewing the content of the site we found that much of the content seemed generated with the intention to look like a plausible site for a project such as ours, using influence from the actual Github project to populate content around the site. There didn’t seem to be other clear downloads or any unexpected Javascript loading. We also noted that the domain had been registered June 18th, 2025; so whatever was going on seemed to be relatively new still.

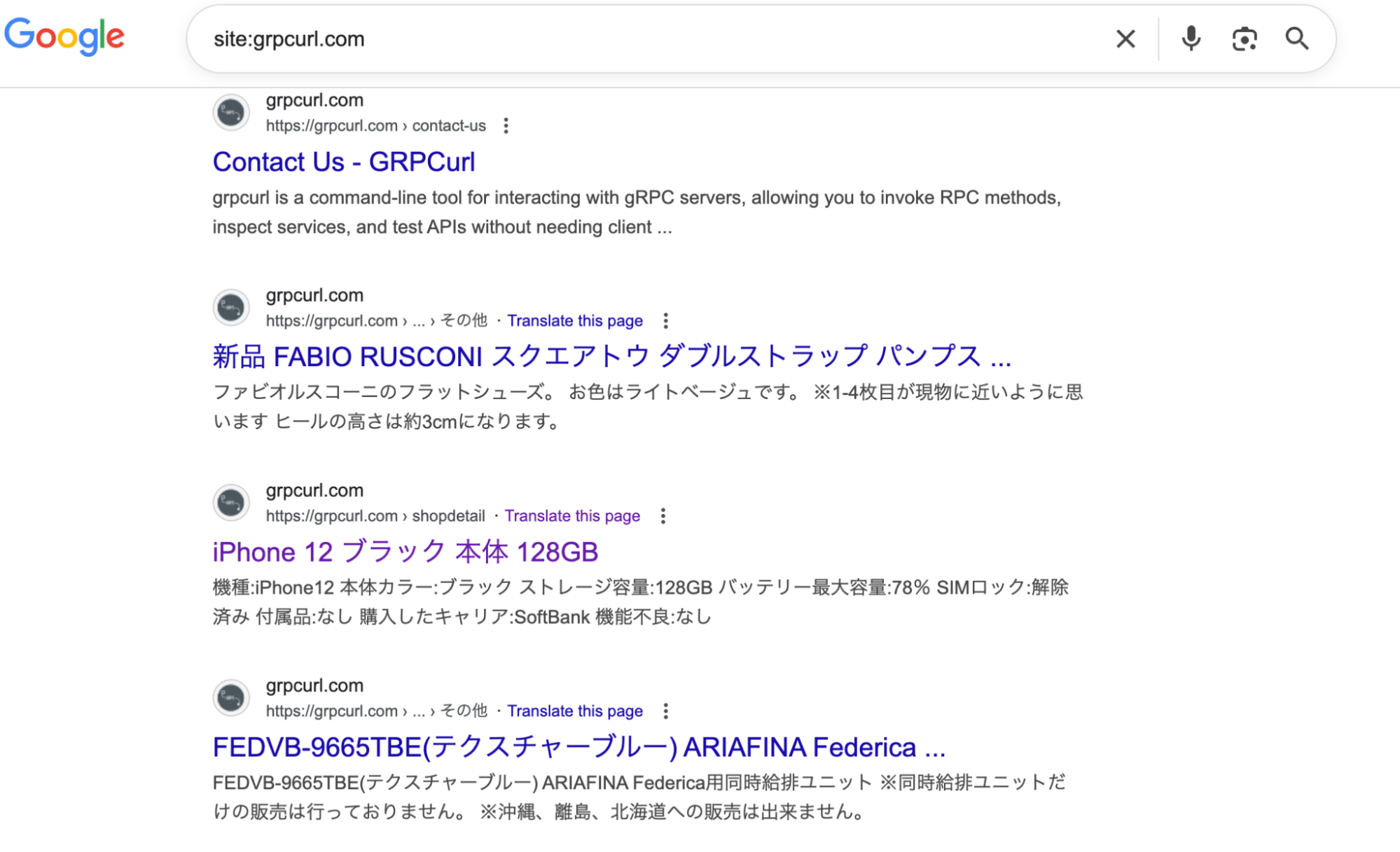

We then decided to check for what Google knew about this site, using the site: prefix to find all indexed pages for the domain. This led to us seeing dozens of results for /?shopdetail/XXXXX pages that were Japanese-text shopping pages for various technology and fashion brands. Trying to load those links however did not actually take us anywhere, which could be explained a few ways – such as out-dated results, pages served only to search engines bots, or similar. It also could be indicative of a default vhost configuration leading to those to be served off a shared web hosting configuration. Unfortunately this site was being proxied via Cloudflare, meaning we did not directly know where the site was being hosted to learn more about it.

Are we alone?

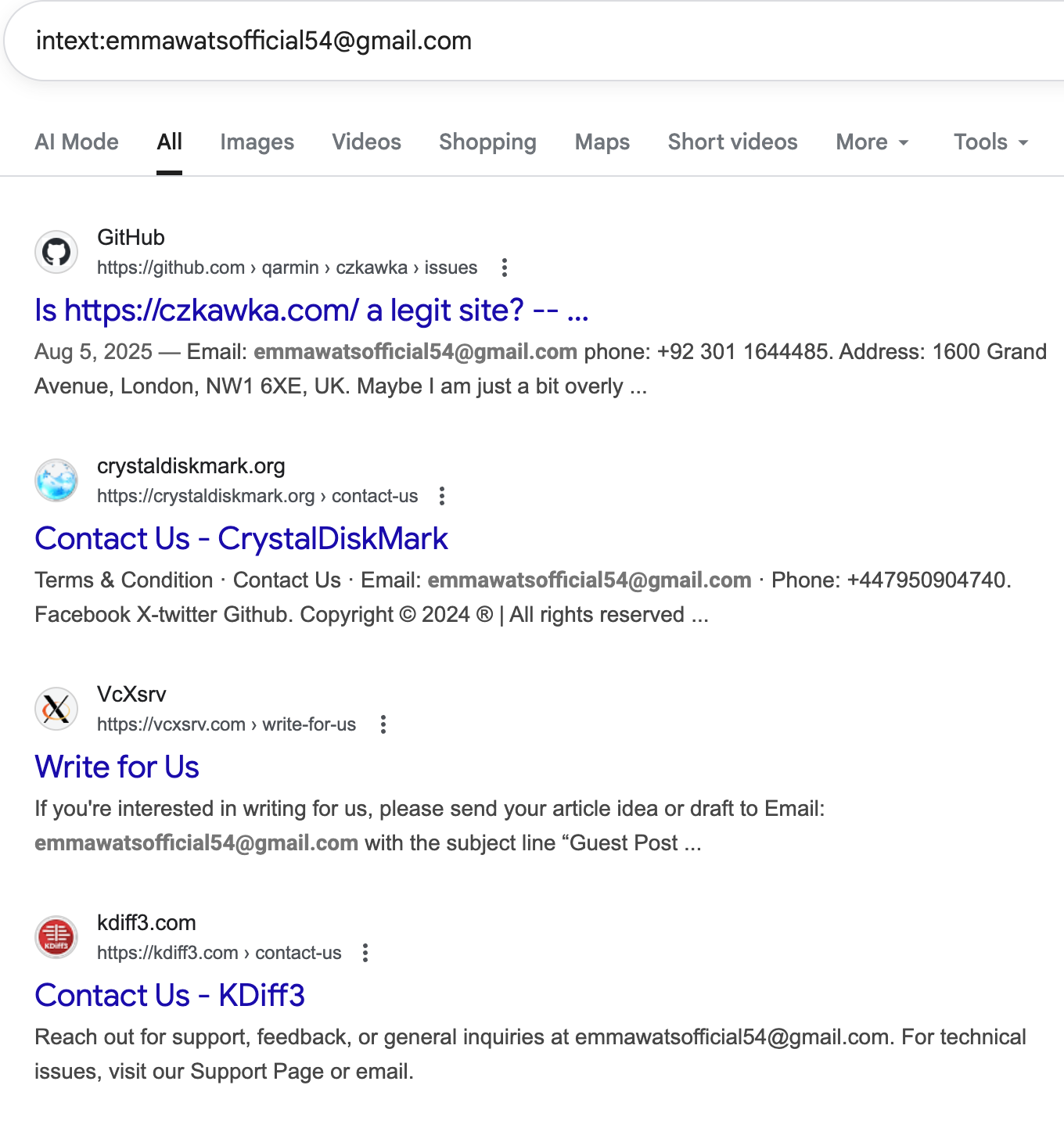

Without seeing any direct abuse from this site – but obvious indications it may be tied to other shady business such as fraudulent web stores – we next tried to see if this was more of a targeted focus on our company/project by identifying any references that may be unique. Importantly, the site provided both an email address (emmawatsofficial54[@]gmail[.]com☣️) and a WhatsApp (hxxps://wa[.]me/447950904740☣️) link. Using those as indicators, we went back to Google to find those strings via intext: queries to find any results that may be available.

We were not disappointed.

It turns out that those indicators were very popular and resulted in finding other impersonation domains for predominately open-source projects and free software applications. As we found new sites, we also found new indicators by exploring contact link pairs that were different. Ultimately we ended our search process identifying a large set of indicators, including:

8 email addresses

11 phone numbers

2x United Kingdom (+44)

9x Pakistan (+92)

1 WhatsApp account

3 Telegram accounts

We aggregated all of our unique domain findings and came up with 165 web sites matching 1-or-more of these indicators. Further, the vast majority of these sites we had indexed were created with WordPress and had a similar generic content format. This group served to be the basis of the next phase of our analysis plan that we would further pull together resources.

Who else is being impacted?

One of the first things we saw in our search result analysis was that there were threads among open-source projects, Reddit, and other sites flagging some of these domains as fraudulent.

For instance, on September 9th, 2025, the open-source project minimap2 – which “aligns DNA or mRNA sequences against a large reference database” – added a commit to their README file noting that a fraudulent domain for their project existed and was considered a phishing site.

On August 5th, 2025, a user of the open-source file clean-up tool Czkawka created a Github Issue for the project asking about the legitimacy of a domain related to that project. This led to a larger discussion about the risks involved of this impersonation and noting some of the other projects that users had noted were related to some of the indicators that we had also seen.

Of the 165 sites we had aggregated in our search effort, we generically categorized them as:

67 Open-source Projects

46 Free Software

28 Online Tools

23 Blogs

We also tried to map the “real” project or web site that the domain we found would be attempting to impersonate. Of the 165 we found that 118 seemed to have a clear match. The other sites were either too generic to narrow down a 1-to-1 match, or seemed to simply exist as a content web site without having an obvious, direct impersonation to any existing web site or project.

As a sampling, here are ten of the most notable impersonating domains we found in scope:

ghidralite[.]com☣️– represents the National Security Agency’s project, Ghidra, that has over 61k stars and is used for reverse engineering by many security professionals

deepseekweb[.]io☣️– represents the notable Chinese AI company, DeepSeek, that provided popular foundational models and has many Github repositories over 50k stars

geckodriver[.]org☣️– represents Mozilla’s project, geckodriver, that is often used by software engineers to automate Gecko-based browsers (e.g. Firefox) for web site testing

getimagemagick[.]com☣️– represents the popular open-source project ImageMagick, which is used for digital image editing in many applications and has nearly 15k stars

getsharex[.]org☣️– represents the productivity tool, ShareX, which features screen capture and recording functionality, along with filesharing, and has nearly 35k stars

helixeditor[.]com☣️– represents a Rust-based text editor, Helix, that is focused on software engineering end-users and has over 40k stars for its repository

mtkdriver[.]org☣️– represents MediaTek’s Windows-based software, MTK Driver, that is used for helping allow MediaTek’s phone and tablet devices to communicate to a PC

radminvpn[.]org☣️– represents Famatech Corp’s free software, Radmin VPN, that is stated to have over 50 million users to allow them interact with VPNs on Windows

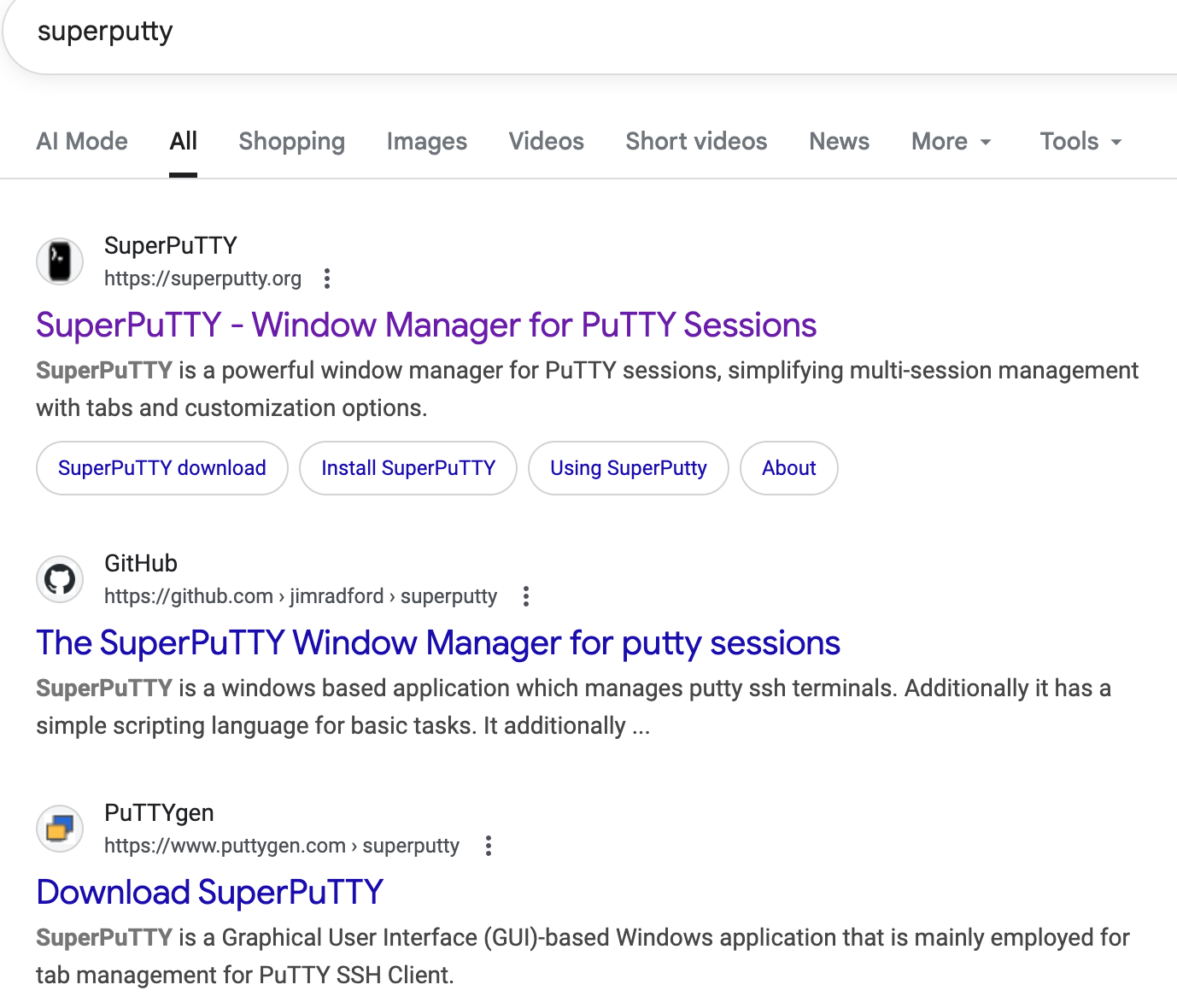

superputty[.]org☣️– represents a Windows utility called SuperPuTTY that improves the SSH and RDP profile configuration experience for the popular technology, PuTTY

vncviewer[.]org☣️– represents Real VNC’s technology, VNC Viewer, which has existed since 1998 and used across organizations around the world for remote system access

winra1n[.]org☣️– represents a Windows frontend called WinRa1n, which acts as a way to more easily jailbreak Apple iOS devices (e.g. phones, tablets) using known exploits

Gathering data from our domain list

For each domain we had found, the following data was gathered to maintain offline copies:

Domain registrations (e.g. whois)

Active DNS records (e.g. dig)

Historical DNS records (e.g. DNSDumpster.com)

Recursive web site archive (e.g. wget)

Certificate transparency logs (e.g. crt.sh)

Google page listing (e.g. site:foobar.com)

WordPress meta data (e.g. wpscan)

Screenshots of home pages (e.g. selenium)

Google references to domains (e.g. intext:foorbar.com)

Archival site history (e.g. Wayback Machine)

Each of these data sets were then either cataloged into spreadsheets or stored as archival copies in a project folder so that research questions could be asked without worrying about drift in data from domains changing providers, being taken down, or having major content updates.

Building a timeline of domains

The most accessible source of information about the history of this campaign is to simply look for relationships between WHOIS records for each domain, understanding when and where they were created. Using our original 165 domains found with our indicators list, we saw that 141 (85%) were registered with one-of-four domain registrars. 150 (91%) had registrations in 2024/2025. All the other domains we saw out of those groupings appeared to be related by indicators, but did not necessarily align with the general focus on free/open-source software.

We also pulled data from the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine and found that 19 (12%) of sites were first indexed in 2023, 79 (48%) in 2024, and 18 (11%) in 2025, with the remainder spread across many other years, likely from prior registrations of the domains that lapsed.

The goal of these impersonating domains

In a word? Money. These domains are focused on gaining favorable search engine rankings by leveraging the name, brand, and popularity of the original web sites and projects. As noted, many sites are in the top rankings on Google for the relevant search term, often eclipsing the real project’s web site. This makes their visibility an asset and can maximize links and content.

During analysis we were able to easily track down the originating company and owner of the primary business behind these domain registrations. In fact, we found a domain list that matched a majority of the ones we had organically found, tying back a direct, “pay to post” price list and SEO meta data for domains that were in scope for our research. This was further correlated to some information leaks from unprotected WHOIS records, WhatsApp accounts, phone numbers, emails, and other publicly available resources. Furthermore, some of the project owners we had contacted were also confirming their awareness of this information.

100 of the 165 sites we had organically found were directly linked to one pay-for-play list. The remainder shared indicators (e.g. emails, WhatsApp, Telegram) that had a strong relationship.

For our project’s impersonation domain, a post was listed as a “General” for $20 and “Premium” for $35. They listed the Domain Authority as ‘24’, Domain Rating as ‘31’, and Traffic at ‘500’. The purported Turn-around Time is ‘Instant’ and Link Type as ‘2 Do Follow - Permanent’.

We do not have any belief that these domains are being actively used for any purpose other than content generation to drive traffic and allow third-parties to gain publicity for their own sites and content through purchasing access to linkbacks and publication of desired posts. That all said, there’s more to this problem than an original intent for each of these domains.

Framing the layers of harm

Nearly half of the 118 sites we ended up focusing on were hosted on Github or Sourceforge, highlighting their open-source involvement. For the remainder, most were some type of freely available application or web service offering. This context is important because it highlights the targeted sites are often not commercial in nature and therefore less equipped to take action.

Small projects are a soft target for fraud

While some open-source projects are maintained by a commercial business entity, most projects operate as a community-driven, volunteer collaboration. To resolve the type of domain impersonation involved here will generally require:

Experience – directly or via legal counsel – in trademark management and defense

Funding of hundreds-to-thousands of dollars to properly file ICANN takedown paperwork

Volunteer leadership to take on the responsibilities that exceed software development

Working knowledge of forensics and investigative techniques to determine providers

In communicating with many of the original web site/project owners, we’ve heard specific complaints that validate the list above – it’s frustrating and victories for this are often fleeting

“This is a hobby open-source project though, so there's very little I can do about any malicious third-party domains.”

“You're correct, this domain is indeed impersonating my project's repository. I did notice this scheme myself a few weeks ago, but at the present time I don't have the resources to deal with this myself.”

“I'm aware of the web site and I've had their various hosting companies suspend their account about 4 times. They just keep moving to new hosting companies.”

Even free and open-source projects that are maintained by parent organizations, the time, effort, money, and legal counsel required to successfully eliminate this problem is prohibitive as the sheer number of open-source projects a company could have impersonated can easily exceed practical limits. The ability to register domains cheaply is dramatically easier than the takedown.

Security risks at every turn

Security professionals reading this post are probably spinning by now with the potential for abuse in how these domains are being created, hosted, and managed. A few concerns exist:

Phishing campaigns

Each fraudulent domain – which in many cases is the literal project name, or even a different gTLD for a real domain name – could rapidly be used to send convincing emails. While we have all seen obviously bad phishing domains attempted, this problem is a bit different as the focus on SEO has led to some of these fraudulent domains being indexed on Google higher than the real project. In this example, SuperPuTTY – a project that will help system engineers perform remote administrative connections – has its real project site as the second result below the impersonation domain. Most people that search for this domain would likely take that as proof.

Supply chain attacks

As noted previously, many of the projects involved in this campaign target projects that have a tie-back to software engineering, systems administration, network access, and cybersecurity. As we have archived during our analysis, most of these sites were directly hosting software with download links for web sites that they are impersonating. This means that an unsuspecting user could use a search engine to find this fraudulent web site, see a download link, and directly run software from a web site that has no actual affiliation with the project they believed it to be from.

The cybersecurity industry is well aware of ongoing, focused efforts to compromise the very types of open-source software that so many of our findings relate back to. But in practice when software engineers are simply trying to do their job, they are up against threats that have real consequences if they happen to unknowingly utilize a backdoored software dependency or tool. This is even easier to accomplish when the source of the technology has a convincing domain and a robust amount of content, including downloadable software. Students, engineers, system administrators, and numerous others are all at risk to be fooled by domains such as these.

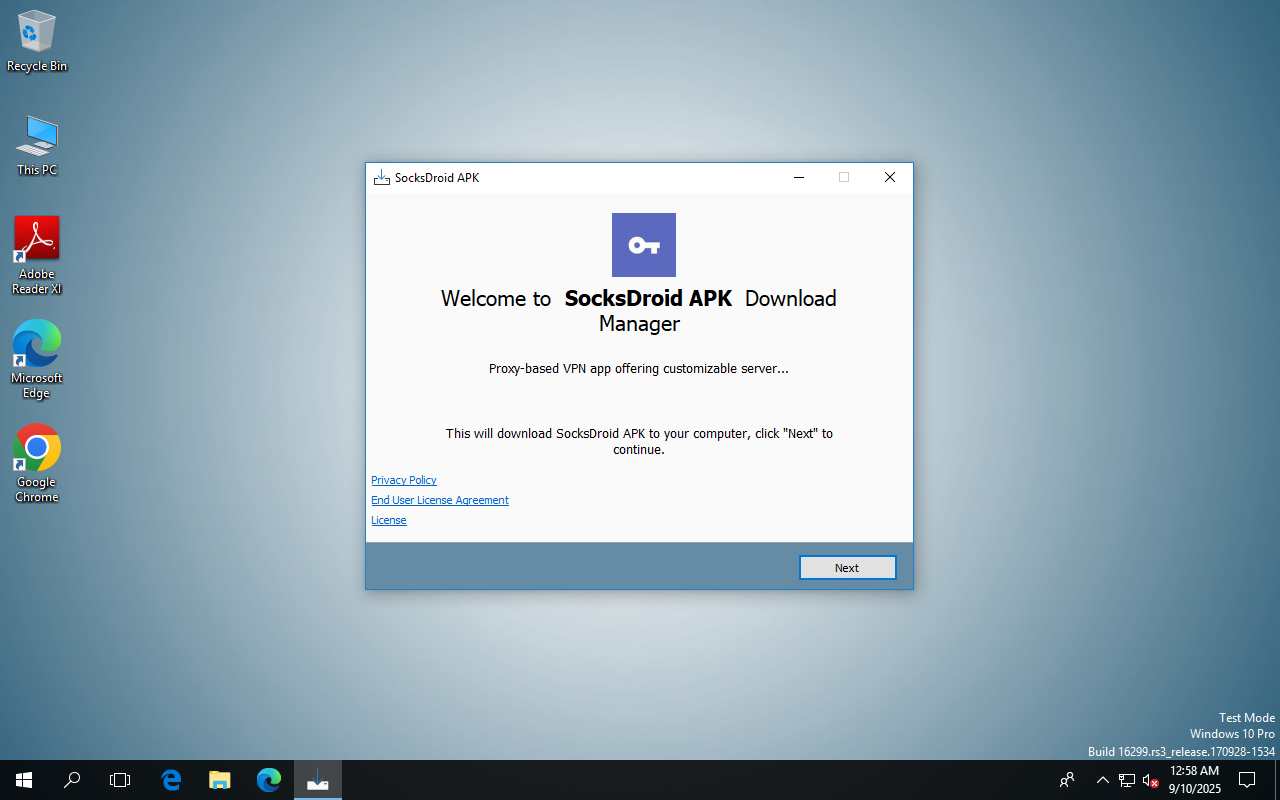

From an analysis of all downloadable files across these sites, 36 files were flagged by VirusTotal as having 1-or-more malicious detections. In practice we don’t know if the original files that were used to host on these impersonation domains also had any detections. By hosting these files – and doing so on domains intending to look authentic – end-users are now left to determine what the authoritative source of software even is. Even if the copies are authentic today, the risk is that these files are swapped out later for malicious copies. Software hosted by these sites is also unlikely to be readily updated when releases come out, so if a security vulnerability exists in a released piece of software, users could still be downloading outdated, unpatched copies.

The above screenshot comes from a sandbox execution of an executable that was hosted on a fraudulent domain of a real project SocksDroid that should have been an Android APK mobile application. Once this software runs, it launches a browser window for a remote web site to download software. While we did not do exhaustive testing of each application that was hosted on each domain, it’s clear that a Windows executable for an Android APK is not very expected.

Watering-hole attacks

Even if no malicious intent exists by the owners of these domains, a third-party attacker wanting to abuse the discoverability and brand of one of these sites – such as the domain pretending to be the NSA’s Ghidra project – may attempt to hijack the domain or host malicious files if they could compromise the CMS (WordPress, mostly) or hosting provider.

Each of these domains are opportunities to take advantage of the implicit trust and efforts put behind making these sites look official and become indexed on search engines. In multiple cases during this research, our own team lost track of which site was real-or-fake until we spotted some of the tell-tale signs (e.g. a contact email address) to denote the fraudulent site.

When reviewing the hosting configurations of each domain, we noted that nearly every site was clearly running WordPress as a CMS to operate the site. Of those sites, 185 individual findings for out-of-date plugins or themes were noted. In the case that these components are not patched for security vulnerabilities – let alone the security of the hosting providers used – an attacker may find a way to compromise these sites and host their own files or content pages.

Our efforts to help the community

While this fell onto our plate simply because one of our projects was targeted, it became apparent through our analysis that this was causing real confusion and concern, with little recourse for an average project owner to take steps at improving their own situation. Organizations such as Google (via the OSS VRP), the EFF, and the Software Freedom Law Center all find ways to support the open-source community and we think that similar to their efforts, we believe that making small improvements for our community is the right thing to do.

Once we had determined the scope and scale of this campaign, we performed some next steps that would hopefully reduce the number of impacted projects or at least increase awareness:

Notified a representative for each real project about the impersonation domain

Filed requests for Google and Microsoft to flag each web site as being untrustworthy

Contacted eight domain registrars with a list of domains they were in control of

Contacted seven hosting companies and network owners of in-scope IP addresses

We received back communications from a handful of domain registrars and providers across the 118 domains that were focused on for our outreach around this issue. What was the impact?

58 total web sites had their hosting suspended by the original provider

6 domains were suspended by the domain registrar in control

This means that 64/118 (54%) of our focal domains were either permanently or temporarily impacted. In practice, 109/118 (92%) of sites were being proxied via Cloudflare, making the determination of hosting providers difficult – but not impossible. In many cases, IP addresses were leaked via DNS records (e.g. TXT, MX) that point in a direction to provide an abuse email.

Since that time the majority of these domains are now being hosted again – a result we certainly expected and unfortunately matches the experiences of the real project owners. We do hope that a much larger number of project owners are now informed about this issue and will take their own steps – as time and financial support allows for – to reduce this problem on their end.

Changes by the impersonating domain owners

We’ve also seen changes in the web sites that are being hosted on many of these domains:

Web sites – including one related to our project – are now showing a disclaimer at the bottom of the site that reads, “Not affiliated with GRPCurl. This is an independent site providing documentation, guides and links to the official project repositories. For official releases visit GitHub” ; this is a change only made after the domain was suspended

The previously self-hosted files being served by these impersonating domains appear to be moving to a model where they are instead linking directly to the authentic project

Original Footer (September 2025)

Current Footer (October 2025)

We are glad to see that there may be small changes that will help to disambiguate the authenticity of these sites and reduce the risk of someone downloading outdated or insecure software from these domains. However, the entire purpose of these sites are to be indexed on search engines, receive traffic, and represent content that will still confuse most end-users.

In conclusion

What started as a simple email to us certainly captured our attention for many weeks as we gathered information, uncovered context, and ultimately drove to action for these projects. It was frustrating to hear back from project maintainers and small business owners that they felt hopeless and uncertain about how to even proceed in their own situation. It’s an unfair burden to put such vulnerable communities at risk of harms that are derived simply from trying to make a few dollars off their hard-created brand, public reputation, and contributions to free software.

The ease of templated CMS building, AI-generated content, and web scraping technologies make the creation and enrichment of sites like this cheap to build and maintain. We already know that AI-supplemented phishing campaigns are on the rise and improving the quality of messaging, which should provide for even more focus to combat impersonation domains.

We hope that the awareness of this campaign – and the many others like it – will allow project owners to be vigilant about the domains registered under their name by keeping an eye out for unexpected search results, complaints by community members, and other monitoring activities.

As they are able, we would encourage project owners to understand their opportunities to resolve their own instance of this problem, including following ICANN’s processes for Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) and Uniform Rapid Suspension (URS). They may also want to contact the current domain registrar, mark sites as unsafe with Microsoft and Google, and reach out to any known hosting providers. Lastly, please inform your communities via a pinned post, README update, or other outreach paths when sites are found to exist.